The Rights of Muslims: America’s Incomplete Story

The White House Politics and the Future of Muslims

In the United States, public opinion polls are commonly used to predict who the next occupant of the White House will be and to gauge the popularity levels of presidential candidates. Are these surveys accurate? The answer becomes clear in the days following the election results. For instance, after the recent U.S. election results were announced, organisations that had predicted Trump’s victory faced opposition from critics who dismissed such surveys as mere propaganda aligned with Trump’s campaign.

These critics not only reassured their own supporters but also continued to publish surveys in favour of their candidate, Kamala Harris. However, was the inhumane treatment of Palestinians in Gaza by Israel, which remained a significant topic of discussion, a factor contributing to Kamala Harris’s defeat? This cannot be stated with certainty.

Let us explore whether Muslims, amidst the prevailing atmosphere of Islamophobia in the U.S., can influence future American elections and examine the history of Muslims in the United States.

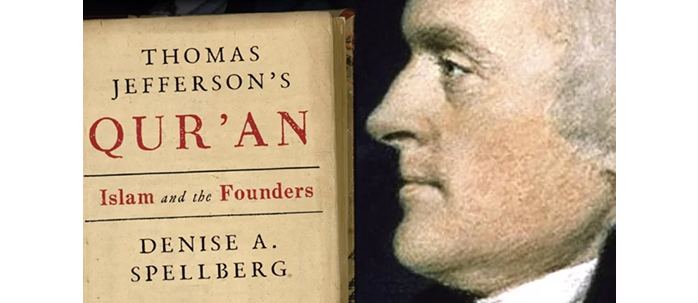

Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States and author of the Declaration of Independence, not only owned a copy of the Qur’an but also envisioned Islam as a possible part of American society. He advocated for the protection of Muslims’ rights and saw them as potential citizens of the new American state. Jefferson purchased a copy of the Qur’an eleven years before drafting the Declaration of Independence, and his Qur’an is still preserved in the Library of Congress, symbolising the early connections between Islam and America. These connections continue to hold significant importance for candid American scholars even today.

Jefferson’s possession of a Qur’an suggests an interest in Islamic teachings, though it does not necessarily imply he aimed to address Muslims’ specific issues. Jefferson’s initial understanding of Islamic principles of basic rights was influenced by the writings of the seventeenth-century English philosopher John Locke, who encouraged European societies to incorporate Muslims and Jews. Locke was following the insights of thinkers from a century earlier who had already considered this. Jefferson’s concept of Muslims’ rights can be better understood within the context of intellectual developments across the Atlantic from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century.

When sectarian conflict arose among Christians in Europe, some Christians viewed Muslims as a means to test the limits of tolerance toward followers of different beliefs. These European precedents made Muslims a subject of discourse in America as well, particularly concerning “the boundaries of citizenship and tolerance.” During the formation of the new government, America’s founders—all Protestant—considered examples from the Islamic world while deliberating on religious freedoms for people of various faiths. Founding American thinkers debated whether the United States should be predominantly Protestant or openly accept followers of all religions. They even thoroughly discussed whether non-Protestants should be allowed to attain high offices, like the presidency. These considerations inspired reflections on religious freedom and the idea of separating religion from the state, as well as discussions around religious tests in the Constitution, which persisted in some states into the nineteenth century.

The notion of resistance to Muslim citizenship was not surprising in the eighteenth century. Americans inherited nearly a thousand years of negative European perceptions regarding religious leadership and politics. Yet, despite the negative sentiments surrounding Muslims, it is remarkable that some of America’s most prominent early figures rejected the idea of excluding Muslims as potential citizens. The Founding Fathers envisioned Muslims as citizens with full rights, a stance that mirrored a thousand years of European political thought and extended it further. This raises the question: how did the idea of fully recognising Muslims’ rights survive in America despite resistance? And perhaps more importantly, what future does this idea hold in the twenty-first century?

This book provides insights into the views of prominent early American figures regarding Islam, showing that they refused to accept negative opinions about Islam as definitive. While Europe subtly encouraged intolerance toward Islam and Muslims, these figures declined to adopt that view.

Most American Protestants believed that Muslim beliefs were unacceptable. This mindset fostered a status quo among Protestants while also encouraging some Americans to consider the value of listening to diverse perspectives. As one part of society resisted the inclusion of Muslims, a growing segment began to see the benefits of welcoming people of various faiths, promoting a more inclusive society. This evolving mindset gradually fostered an awareness that Muslims, too, could be embraced.

Such considerations emerged even before Muslims had arrived in America, with acceptance of them being cultivated in advance. Jefferson and his close associates understood that thinking and debating about Muslims’ rights would pave the way for universal rights in America. Consequently, the acceptance of minorities, including Catholics and Jews, advanced within the mainstream of society. The discussions about Muslims’ rights helped establish the notion that all people should be welcomed with an open heart.

America gained true independence from Britain in 1783, and in that year, George Washington wrote to Irish Catholics residing in New York, emphasising that America should welcome individuals of every religion and sect, especially those who had suffered persecution. At the time, America had only around 25,000 Catholics, who faced significant restrictions, including political exclusion in New York. Washington also wrote to the Jewish community, then comprising only 2,000 individuals in America. He envisioned America as a haven for the oppressed worldwide, especially those persecuted for their beliefs.

In 1784, George Washington openly expressed his views on Muslims at his home in Mount Vernon. A friend from Virginia had written to him about needing a carpenter and a mason for house construction. Washington replied, explaining that the religion, sect, colour, or race of a craftsman was irrelevant in building a house or making furniture. A good craftsman could be from Asia, Africa, or Europe and could be Muslim, Christian, or Jewish, or even have no religious beliefs at all. This letter highlights that Washington included Muslims in his vision of “America for All.” He may have sensed that Muslims were unlikely to play significant roles in various fields for a long time to come.

Different sources suggest that Muslims were living in America during the 18th century, though Thomas Jefferson and his associates seemed unaware of their presence. Jefferson and his colleagues had referenced Muslims as potential future citizens of the United States. Mentions of Muslims in the writings and speeches of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were certainly intentional. Both of these influential figures inherited two contrasting European perspectives on Muslims.

One perspective argued that the teachings of Islam were entirely opposed, even hostile, to those of Protestant Christianity and that Islamic ideas contributed to oppressive regimes. Accepting Muslims into America’s Protestant society meant including a community whose religion and related views Europe deemed alien and dangerous. This was not limited to Muslims; American Protestants similarly regarded Catholic beliefs as foreign and hazardous, as Catholicism was also perceived to oppose American ideals of freedom and inclusivity.

Jefferson and other advocates for non-Protestant citizenship fostered a school of thought that opened the door not only for Muslims but also for Catholics and Jews. In the 16th century, Catholics and Protestants who advocated for their beliefs faced severe persecution, and those who promoted the acceptance of all religions in the 17th century were often sentenced to death, forced labour, or exile. This rejection applied to people from various backgrounds, including aristocrats who embraced all religions and endured harsh punishments for doing so.

Non-conformists in religion were typically unorganised, yet they supported the acceptance of organised Muslims within Christian states as a means to avoid persecution.

As a prominent Anglican establishment member and leading Virginia politician, Thomas Jefferson advocated ideas that had previously subjected their proponents to ridicule or even the death penalty in Europe. Because Jefferson himself was part of the establishment, his views on Muslim rights were taken seriously in Virginia. Alongside a few colleagues, Jefferson presented concepts to the fledgling United States that had been largely dismissed or lost in European mainstream thought. It’s not that Jefferson was instantly celebrated for his ideas on religious freedom for all, including Muslims; opponents challenged him at every turn. However, he also garnered significant support, especially from groups like the Presbyterians and Baptists, who had experienced Protestant repression.

While few in American society were genuinely committed to extending full American citizenship to non-Protestants, there was still a degree of tolerance for Muslims. What these early proponents of Muslim rights were suggesting was novel and largely unaccepted in the 18th-century social landscape, where American citizenship was typically reserved for white, male Protestants. Distinguishing citizenship from religion was essential, and Virginia’s initial legislative steps marked only the beginning of a long journey.

Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, and James Madison began the work of separating citizenship from religion, a formidable task. Despite substantial effort throughout their careers, they couldn’t fully achieve this ideal and left it as an unfinished mission for future generations. This book is the first to explore how Jefferson and his peers, despite their incomplete and sometimes ambiguous understanding of Islam, were active in advocating civil rights for all non-Protestant citizens, including Muslims.

In 1784, George Washington advocated for allowing Muslims to work in America. Nearly a decade earlier, he mentioned two African women, a mother and daughter, named Fatima and Fatima Sughra, who were part of his taxable estate. Although Washington supported granting Muslims American citizenship, the reality is that he himself bought Muslim slaves, thereby obstructing their fundamental rights. Notably, at that time, enslaved Muslims were not allowed to practice their religion. This may have been the case on the estates and farmlands of Jefferson and Madison as well, though we have little information about the religious background of their slaves.

There’s no doubt that the number of Muslim slaves brought from West Africa was in the thousands, possibly even surpassing the number of Catholic Christians and Jews in America at the time. Some former Muslim slaves may have even served in the Continental Army, though there is no evidence that they practised their faith, nor that the Founding Fathers were aware of their presence. It’s also noteworthy that these former Muslim slaves did not influence the debate over Muslims’ civil rights or citizenship rights.

Although Muslims had been present in America since the 17th century, racial and slavery-based factors were so strong that their religious identity remained largely hidden. When the Founding Fathers thought of the rights of future American Muslims, they likely envisioned only white Muslims. By the 1790s, any white person, regardless of their background, could apply for American citizenship. Jefferson met only two Muslims, both ambassadors from North Africa of Turkish descent. He neither commented on nor wrote about their appearance; both were relatively fair-skinned. Jefferson’s attention to these ambassadors was due to their political and diplomatic status rather than their race or religion.

As ambassador, Secretary of State, and Vice President, Jefferson avoided viewing America’s conflicts with North African states through a religious lens. American shipping was constantly threatened by piracy in the Mediterranean and eastern Atlantic. Jefferson clarified to the rulers of Tripoli and Tunis that his nation harboured no anti-Islamic prejudice. At one point, he even remarked that Americans worshipped the same God as Muslims.

Jefferson wished to separate religion from politics and governance, a principle he advocated both domestically and internationally. His perspective on Islam and Muslims was largely shaped by relations with the North African states, forming the basis of his foreign policy in that region. It’s also possible that Jefferson, being a monotheist, felt some affinity with the Islamic world.

While Jefferson certainly would have been aware of the prevailing negative perceptions of Islam, it’s likely that he used certain inherited European notions and examples in the Virginian debate on separating religion from state affairs. The ideological victory Jefferson achieved between the 18th and 19th centuries remains a challenge for Americans in the 21st century. Since the late 19th century, America’s Muslim population has grown significantly, exhibiting rich ethnic diversity. However, American society has never fully embraced Muslims. In Jefferson’s era, an imagined Muslim population faced prejudice; in today’s America, Muslims are subject to political hostility.

The 9/11 attacks and the War on Terror have cultivated an environment in which many Americans support restricting Muslims’ fundamental civil rights. Today, there is growing debate about whether a Muslim can qualify to be the President of the United States. This question first arose in connection with Barack Obama but actually dates back to the early history of the American presidency. Jefferson was the first prominent figure accused of being a Muslim.

The question of whether an American Muslim can be President helps illustrate the degree to which Muslims have permeated the American public consciousness and how Muslim rights became an early component of American ideals. Thus, understanding the debate on Muslim rights that began in the late 18th century is crucial to understanding the contemporary issue of Muslim citizenship in America.

While the rights of American Muslims were theoretically recognised long ago, they still face significant trials in practice. In fact, American Muslims experience challenges regarding their rights on a daily basis. In today’s America, even prominent scholars such as historian of Islam John Esposito have been compelled to question the supposed Western tolerance and inclusivity. Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an helps us understand when, where, and how Muslim rights were incorporated into American ideals.

Historians have spent considerable energy trying to prove that Islam and American ideals are fundamentally incompatible. Many argue that Protestant Americans have consistently dismissed Islam as inherently un-American. Some historians even suggest that America itself was born in the 18th century as a reaction against the oppressive governance structures attributed to Islam. Certainly, America’s early policies and documents contain traces of this viewpoint. However, there are also positive views of Islam and Muslims, such as the discourse on the “rights of future American Muslim citizens.” This implies that not all Protestants viewed Islam as an entirely foreign faith.

This book sheds light on the fact that Muslims were not only non-American but that discussions regarding their potential citizenship and expected rights had already taken place at the time of the country’s founding. However, it is true that many of these ideals were not openly accepted by the majority of Americans at the time. Alongside exploring Jefferson’s views on Islam and the Islamic world, this book also eloquently presents the thoughts of John Adams and James Madison. The discussion about the rights of Muslims was not limited to the Founding Fathers. The struggle of Baptists and Presbyterians in Virginia, as well as their confrontations against the religious establishment, are also detailed in this book, along with the advocacy for Muslim rights by the well-known Anglican lawyer James Iredell and Samuel Johnston. The evangelical Baptist John Leland, who was among Jefferson and Madison’s associates, raised his voice for the rights of Muslims in Connecticut and Massachusetts. He also protested against the flaws found in the Constitution, the shortcomings of the First Amendment, and the role of religion at the state level.

The Mention of Two Muslim Slaves in America’s History

This book discusses two Muslim slaves from West Africa, Ibrahim Abdulrahman and Omar ibn Said. Omar ibn Said was literate in Arabic and even wrote his autobiography in the language. The mention of these two Muslims indicates that thousands of Muslims were present in America at that time. However, they were deprived of many rights, including the freedom to practise their religion. They were also denied the right to citizenship.

Even in the 20th century, Catholic Christians and Jews continued to struggle for their rights. The rights they eventually secured were not fully aligned with the constitution. However, the bitter truth remains that Muslims are still the only community in America that has not been fully accepted. Even today, efforts are made to limit their influence.

With the Pharaoh of the White House, Trump, recognising Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, there is no longer any room for doubt that this is not only a declaration of hostility against Muslims in America but an open declaration of war against the Islamic world as a whole.

Both candidates in the U.S. elections openly supported Israel in their campaigns. The newly re-elected Trump, once again, expressed his support for Israel to completely destroy Iran’s nuclear programme and promised a strong response to Iran’s missile attacks.

The question now is whether the ongoing Israeli aggression, openly supported by the candidates of both U.S. political parties, will lead the Islamic world to remain silent—effectively committing suicide by allowing the creation of Greater Israel—or whether it will seize this opportunity to reshape its destiny.