The Empire’s Bargain: Kashmir, America, and the Theatre of Deception

Sands of Betrayal: America’s Mediation and the Muslim World

The question of Kashmir stands as one of the most enduring and intricate disputes between the two principal nations of the Subcontinent—Pakistan and India—its embers fanned intermittently by the world’s major powers. Foremost among them is the United States, which has at times presented itself as mediator, at times as a strategic partner, and at times merely as a spectator of convenience. This paper seeks to illuminate the historical landscape within which Washington’s overtures to arbitrate were made, the expectations entertained by the Pakistani state, and the often-perverse outcomes that ensued.

History, that silent chronicler which never lies—provided it is read by minds schooled in reflection—records with unflinching clarity the political evolution of South Asia. In the labyrinth of Indo-Pak relations, America’s role is a chapter repeatedly shrouded in the mirage of hope, only to dissolve in the fog of disappointment. The present analysis retraces those very twists and turns in which American mediation, Pakistani anticipation, and Indian calculation were so tightly entangled.

It is one of history’s iron laws that in global politics there exist neither perpetual allies nor eternal adversaries; interest alone is the final arbiter. And judged by this measure, the world’s most powerful democracy— the United States—has revealed time and again that once its strategic aims are secured, it does not hesitate to sacrifice those very partners who once risked their own security for Washington’s designs.

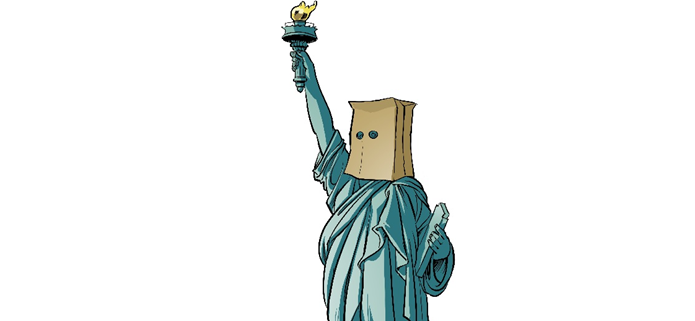

The moves played upon the world’s diplomatic chessboard are often deadlier and more intricate than those in any game of kings. When America—merchant of peace by self-proclamation—dons the cloak of arbitration while holding in its hand the scales of its own advantage, the oppressed often receive the same cold bargain a living soul might obtain from a trader without conscience: “Be silent, surrender the land, and leave the rest to us.”

Those with discernment know well that every page of the Subcontinent’s recent past bears witness to a recurring sorrow: whenever Pakistan lit the lamps of hope and resolve in anticipation of American support, the winds shifted so capriciously that neither the flame survived nor the oil remained. The milestones of the past stand as grim reminders of how Pakistan, time after time, laid its treasure, strength, and trust at the feet of “Uncle Sam,” only to receive in return a few perfunctory assurances and a handful of patronising “advice.”

One recalls that in the autumn of 1962, as Indian and Chinese artillery thundered across the Himalayan frontier, voices of sober calculation in Pakistan’s corridors of power declared, “Now is the time—Kashmir can be regained.” Strategists and commentators urged that India, weakened by its conflict with China, had presented Pakistan with a golden opportunity to take a decisive step towards the liberation of Kashmir. It is said that Beijing, through discreet diplomacy, conveyed similar signals, inviting Pakistan to seize the moment.

Yet Field Marshal Ayub Khan—self-styled and self-assured—chose to repose faith in the pledges of President Kennedy’s administration, adopting a posture of neutrality in the naïve expectation that the United States would later assume the mantle of an impartial arbiter, uphold the scales of justice, and deliver Kashmir into Pakistan’s hands. In this misjudgement—egregious, costly, and historically unforgivable—Ayub sheathed his sword upon the promise of a morrow that Washington never intended to honour. The dream of American mediation proved an illusion, and the hopes raised during the Sino-Indian war of 1962 still echo today in Islamabad’s halls of power as a lament for lost chances and strategic naïveté.

During the 1950s, Pakistan entered the defence pacts of SEATO and CENTO. Though these agreements brought military assistance, the aid was strictly earmarked for countering the Communist threat—not for confronting Pakistan’s regional rival, India. The Defence Agreement of 1959, too, was merely another link in the same chain—offering theoretical protection against Communist adversaries, yet yielding no real advantage on the ground. In essence, these alliances proved unilateral in benefit; Washington gained much, Pakistan almost nothing.

History attests that America, once its objectives are fulfilled, does not tarry in abandoning those allies who served its geopolitical ambitions—militarily, diplomatically, or morally. Pakistan has endured this bitter lesson more acutely than most. The mirage of SEATO and CENTO lured Pakistan down a path whose promised destination proved nothing more than shimmering sand. Under the umbrella of these treaties, Pakistan served as a cog in Washington’s anti-Soviet machinery.

But when war broke out in 1965 and Pakistan took up arms to defend its own territory, the very weapons supplied by the United States were abruptly halted. Washington brusquely reminded Pakistan that the arms were provided “to deter Communists, not Delhi.” Thus, when Pakistan expected practical support during the conflict, it received instead sanctions and suspensions. It was a grim awakening: the United States was never to be Pakistan’s partner against India. And though Ayub Khan had been led to believe that Washington would assume the role of mediator, the Kashmir issue remained precisely where it had stood. The episode was a bitter testament to Pakistan’s position—not as a sovereign strategic ally, but as a pawn upon America’s geopolitical chessboard.

And then came the fateful winter of 1971, when the twilight over Dhaka yielded to a night of national calamity. Pakistan not only lost half its territory but paid the price of securing the release of its prisoners of war by accepting the provisions of the Simla Agreement—whose clauses effectively consigned the United Nations’ Kashmir resolutions to the dusty shelves of diplomatic history. Whether this concession was a necessity or a failure of political wisdom remains a question on which historians will differ, though each narrative carries an unmistakable undertone of Pakistan’s isolation.

India, possessing thousands of Pakistani POWs, bargained from a position of strength. The stipulation that all disputes—including Kashmir—be resolved bilaterally weakened the international standing of the UN resolutions, though it did not erase them. It was, nonetheless, a diplomatic setback for Pakistan.

It is worth recalling that in 1970, General Yahya Khan played a pivotal role in facilitating the historic rapprochement between China and the United States. Yet its “reward” brought neither Kashmir nor the salvation of East Pakistan. The war of 1971 left Pakistan sundered, and the Simla Agreement formalised a clause that diminished the import of the UN resolutions on Kashmir. Bhutto’s diplomacy was celebrated as triumphant, but time has shown that the triumph existed largely on paper, not in the realm of realities.

At such junctures, the words of the Qur’ān offer timeless clarity:

إِنَّ اللَّهَ يَأْمُرُ بِالْعَدْلِ وَالإِحْسَانِ

“Indeed, God commands justice and moral excellence.” (16:90)

Justice, however, has rarely found an advocate among the great powers when weighed against the heft of their interests.

The conflict of Kargil in 1999 once again compelled Pakistan to retreat—this time under the unambiguous pressure of the United States. By then, both nations had crossed the nuclear threshold, and Washington, invoking the gospel of “peace,” restrained Pakistan even as it extended, albeit discreetly, a sympathetic nod towards India. After 9/11, General Musharraf—an adventurer in uniform more than a statesman—capitulated at the weight of a single American phone call. Pakistan committed itself to the so-called War on Terror with such abandon that two of its airbases were effectively handed over to the United States, where Pakistani personnel were barred even from entry.

From these very airfields, according to American records, 57,000 aerial strikes were launched upon Afghanistan; the mountains of Tora Bora were assaulted with munitions scarcely distinguishable from tactical nuclear devices—deployed from the soil of Pakistan itself. In exchange for logistical, intelligence, and ground cooperation, Pakistan received a trickle of financial aid; but it surrendered over seventeen thousand lives, absorbed an economic loss estimated at 110 billion dollars, and carried the burden of hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees—all in the desperate but futile hope of appeasing Washington.

Meanwhile, the United States concluded a landmark civil nuclear agreement with India, cemented a strategic partnership, and to this day India continues—under American patronage—to orchestrate acts of terror within Pakistan. Evidence presented repeatedly before the international community and the United Nations has yielded no meaningful response from the latter, now reduced to little more than a handmaiden of American power, shirking the very responsibilities it claims to uphold.

In 2019, when Donald Trump—ever theatrical—hinted at mediating on Kashmir, he encouraged Prime Minister Imran Khan with the tantalising suggestion that he might “gift the nation a moment of triumph akin to a World Cup victory.” Imran Khan embraced this overture with misplaced optimism. History knocked once more upon our door, yet the pharaoh of the White House soon made it plain that Prime Minister Modi had been granted a free hand to “cash his political cheque” on Kashmir. It became clear that Washington expected Islamabad to stage whatever drama was necessary to secure its own political survival.

General Qamar Bajwa, then Pakistan’s Army Chief, was invited to the Pentagon and accorded an ostentatious 18-gun salute. But behind the ceremonial façade lay a directive: acquiesce to the impending decision on Kashmir. Bajwa’s subsequent briefing to two dozen journalists betrayed a timorous resignation rather than resolve. Trump, in turn, repaid Modi for sharing his stage at two mammoth diaspora rallies, harvesting Indian-American political support during the presidential campaign. Modi, emboldened by American indulgence, revoked Article 370 and declared Kashmir an integral part of India.

To preserve his tenure and lend triumph to his American visit, Imran Khan—echoing Bhutto’s theatrics—ordered party cadres to amass at Chaklala Airbase to enact the charade of a victorious return. Instead of learning from history, we accepted Trump’s mirage of mediation. Upon their return from Washington, Khan and the Army Chief displayed the jubilation of men convinced they had secured a diplomatic conquest. Their staged reception at Chaklala resembled the homecoming of a conqueror. Yet only weeks later, on 5 August, this illusion shattered as Modi dissolved Article 370 and reduced the corpus of UN resolutions to a footnote within India’s own constitution. India had eliminated Kashmir’s special status unilaterally—and America remained silent.

What manner of mediator speaks of arbitration while anointing one party to swallow the contested land? Was this mediation—or a prelude to auctioning maps? If such is the architecture of their diplomacy, then one can all too easily imagine their “solution” for Palestine: hand over Gaza to the United States, let it refashion the territory into a tourist haven in exchange for dispersing the Palestinians across neighbouring Arab states.

The Qur’ān warns with timeless clarity:

فَمَا لَكُمْ كَيْفَ تَحْكُمُونَ

“What is the matter with you—how can you judge so?” (68:36)

At what point shall we recognise the futility of placing faith in those from whom fidelity has never flowed?

A survey of history reveals that since the Second World War, the United States has intervened—directly or indirectly—in more than three dozen nations. Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Yemen—the list is a sombre chronicle of shattered societies. In the end, Washington has either departed in humiliation or cloaked its defeat in the garb of a “partial success.” The return of the Taliban in Kabul and the fall of Saigon stand as indelible monuments to these truths.

During his electoral campaign, Trump had vowed to extricate America from “endless wars.” Yet upon assuming office, his demeanour transformed. Threats were flung at Canada, Greenland, and China; grievances aired against NATO; pressure exerted upon the European Union. His carte blanche to Israel on Palestine, and his silence on the brutalities in Gaza, exposed the gulf between his rhetoric and his actions.

America’s trade war with China ultimately ended in retreat. The endurance of Beijing’s economic model and its expanding global influence forced Washington to temper its ambitions. Meanwhile, in recent Indo-Pak hostilities, the myth of Western military superiority began to unravel. Israel’s alliance with India became starkly visible. Pakistan not only downed Israeli-origin Harop drones but demolished their operators and ground stations within India. The supposed invincibility of American-Israeli military technology evaporated. The furtive repatriation of Israel’s eighteen fallen specialists confirmed what the world had begun to suspect: the much-advertised supremacy of Indian and Israeli weaponry was but a puff of manufactured legend.

In the aftermath, the United States intervened hurriedly to press for a ceasefire—at Israel and India’s urging—to rescue its partners from complete humiliation. For Pakistan, however, this was no new encounter. From 1962 to 1965, from 1999 to 2019, Washington offered the same temporary reassurances, the same chalk-upon-water promises, while the realities on the ground remained stubbornly unchanged. The situation in Kashmir not only failed to improve; it grew more entangled.

Now, once again, America has extended the lollipop of mediation on Kashmir. The reality, however, is unmistakable: Washington intends to employ India as a joker card against China. India’s inclusion in the Quad alliance is a calculated pivot of this design. Yet the United States, in repeating this misjudgment, is once more wagering upon a fragile and unreliable partner.

The role America has played in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Iraq—and now Ukraine and Gaza—casts grave doubts upon its credibility as an arbiter of peace. President Trump advised Ukraine to surrender twenty per cent of its territory to Russia in exchange for “American peace.” In Gaza, mediation amounted to the grotesque suggestion that the war would end the moment the Palestinians vacated their own land. Such proposals do not constitute arbitration; they are coercion dressed in diplomatic finery.

Modi’s campaign-trail threats against Pakistan are but the revival of that threadbare rhetoric through which Hindu nationalism is stoked in India. The objective is not merely electoral gain; it is also to ensure India’s active participation in America’s anti-China project—the “Quad.” Yet the United States refuses to acknowledge the stubborn reality that India could not confront China in 1962, and remains equally incapable today. America’s “lame horse,” hobbled by strategic and military frailties, is little more than a pawn upon the chessboard of global power.

America’s past behaviour, present manoeuvres, and future indications collectively reveal a superpower shackled by its own self-interest. Its promises, treaties, and offers of mediation serve short-term objectives alone. The time has surely come for Pakistan to reshape its foreign policy, to cultivate self-reliance, and to recognise that dependence upon any American president—Trump or otherwise—is to chase that very mirage which forever dissolves upon approach.

CPEC represents the new horizon of Pakistan’s partnership with China. When Pakistan embarked on this project—heralded as a “game changer”—China steadfastly supported Pakistan on the diplomatic front, including on the question of Kashmir. And yet, segments of our own elite persist in anticipating some miraculous American intervention, as though yearning for an old wound to be healed by the very hand that inflicted it.

Suppose, for argument’s sake, that the United States were to advance a formula for mediation: to divide Kashmir; to assign Gilgit–Baltistan to Pakistan and the remainder to India; or to declare the entire region a demilitarised state. Would any party accept such proposals? And if they did not—upon whom would Trump’s ursine wrath descend?

Pakistan must understand that external arbitration—especially American arbitration—is a mirage that invariably shatters upon the granite of disappointment. Nations resolve their crises not by surrendering their agency, but through the strength of their own will, wisdom, and unity. Whether the issue is Kashmir or any other national interest, Pakistan must anchor its decisions in its own capability, diplomatic clarity, and internal cohesion. The soft illusions of mediation crumble inevitably before the hard truth of sovereignty.

Washington’s story is the same tale retold with new actors. Yesterday, General Zia sought American benediction to legitimise martial rule; today, others polish their political armour in the glow of Washington’s welcome. Yet every traveller who clings to the finger of Uncle Sam is eventually left unclothed in that marketplace of power where only might is traded.

Even now, should Pakistan trust Trump’s mediation, the likely proposals would be depressingly familiar: “Accept the status quo; recognise whatever part of Kashmir each side already holds—or lease it to us for twenty years, and then we shall discuss matters again.” What self-respecting state could acquiesce to such terms? And if Pakistan declined—what then? Trump’s rage, as the world has witnessed, resembles the crushing embrace of a bear from which escape is rare and breath scarce. America is a mediator only in the sense that a merchant is: it bargains exclusively for profit, even if that profit requires the erasure of entire Muslim populations.

Those who are shown mirages and led into dreams fall either into the captivity of illusion or reveal their ignorance of history. Pakistan must accept that the Kashmir dispute will not be resolved through American mediation, nor through any international platform, unless the nation itself summons sovereignty, resolve, and internal unity. Every American promise conceals a motive; every offer of arbitration, a barter. The moment has arrived for Pakistan to define its path by its geographical centrality, defensive capability, and ideological foundations. Otherwise, history will once more record a deception added to a long ledger of deceptions.

And the final truth—harsh though it may be—is that nations which repeatedly indulge the same dream find it turning either into addiction or despair. We have time and again imagined that some external saviour will plead our case, liberate our jugular vein, or shoulder our burdens. But a vein wounded by one’s own neglect cannot be healed by another’s hand. History’s inscription is unmistakable: only those seek arbitration who have lost faith in their own strength, their own argument, and their own wisdom.

What is needed now is to learn from our past, to judge friends and foes not through sentiment but through reality, and to place national interest at the apex of our concerns. Otherwise, the lollipop—presented in its dazzling wrapper—will continue to deliver nothing but poison.